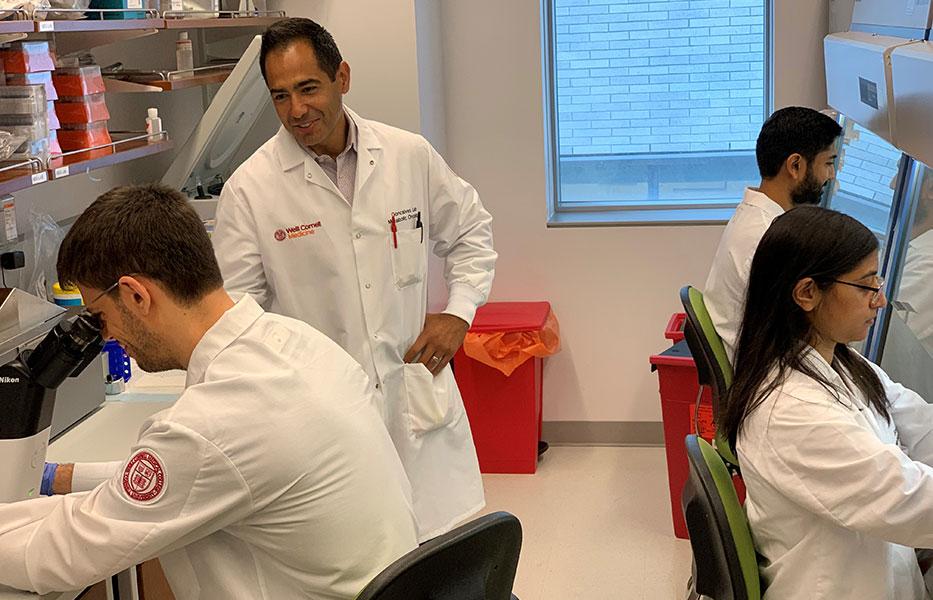

Dr. Marcus DaSilva Goncalves

Dr. Marcus DaSilva Goncalves, Ralph L. Nachman Research Scholar and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, and colleagues have published a paper in Nature that has uncovered a key finding on how fructose in the diet contributes to obesity.

In previous research published in 2019, Dr. Goncalves and team had shown that dietary fructose could increase tumor size in mouse models of colorectal cancer. The researchers had also found that by blocking fructose metabolism, they could prevent that from happening.

In a recent paper published in Nature (August 18, 2021), Dr. Goncalves and colleagues furthered their findings by showing that a high fructose diet directly affects the villi (hairlike structures that line the inside of the small intestine). Villi expand the surface area of the gut, helping the body to absorb nutrients and dietary fats from the food that passes through the digestive tract. The paper’s first author, Samuel Taylor, a Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program student working in Dr. Goncalves’ Lab, made an unexpected initial discovery in the lab’s mouse model. He found that mice on a high-fructose diet had increased villi length.

This discovery led Dr. Goncalves and team to employ a more elaborate tripartite mouse-model that would allow them to learn more. They put the mice into three groups: a normal low-fat diet, a high-fat diet, and a high-fat diet with added fructose. As compared to the other two groups, it was found that the mice receiving a high-fat diet with added fructose developed longer villi (25-40% longer) and became more obese. This discovery has further reinforced the well-known link between rising fructose consumption around the world and increased rates of obesity as well as certain cancers.

“Fructose is structurally different from other sugars like glucose, and it gets metabolized differently. Our research has found that fructose’s primary metabolite promotes the elongation of villi and supports intestinal tumor growth,” said Dr. Goncalves, senior author on the paper. In fact, the researchers found that fructose-1-phosphate, a specific metabolite of fructose, had accumulated in high levels in the mouse model. Furthermore, it was interacting with pyruvate kinase, a glucose-metabolizing enzyme, which was, in turn, altering cell metabolism and promoting survival and elongation of the villus. When this function was removed, the fructose had no effect on villus length.

In future research, Dr. Goncalves aims to confirm that these recent findings in mice translate to humans and to find a way to repurpose already existing drugs that target fructose-1-phosphate in a way that will shrink the villi, reduce fat absorption, and possibly slow tumor growth.

“Fructose is nearly ubiquitous in modern diets, whether it comes from high-fructose corn syrup, table sugar, or from natural foods like fruit,” explains Dr. Goncalves. “Fructose itself is not harmful. It's a problem of overconsumption. Our bodies were not designed to eat as much of it as we do.”

Dr. Goncalves is a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine and an endocrinologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Related Links